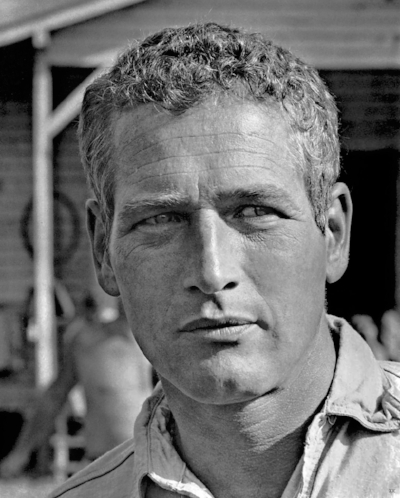

Popular culture can usefully be thought of as a society thinking out loud. It is a running narrative of a nation's collective mind, its conscious and unconscious. If a new word and concept arises -- as cool did in the early 1940s -- then something new is afoot in the world. Cool was a term for a brand new kind of encoded personal rebellion before social movements had mobilized, something you could feel more than explain in the actors, musicians, and writers that turned you on, whether Paul Newman (right) or Sidney Poitier, Miles Davis or Elvis, Jack Kerouac or Lorraine Hansberry. In an insightful review in the hip webzine PopMatters, reviewer Megan Volpert cuts to the quick of cool: "To be cool is to interrogate the social norms that hold us down. It’s a form of rebellion that doesn’t let cards show to police or politicians. Cool is the means by which we can cope with our lived experiences of injustice, a means of enacting hope that after these injustices are unmasked as such, there will be something better on the other side."

Volpert noted my tripartite approach to cool "as a theorist, historian and lover of popular culture [in] a book that synthesizes the best of all three domains." The Origins of Cool in Postwar America is a history of cultural workers -- actors, writers, and musicians -- at a specific moment in time and how their artistic and iconic rebellion sowed political consciousness. In short, a cool rebel draws a public line in the sand against oppression or persecution and his or her action galvanizes an audience or generation.