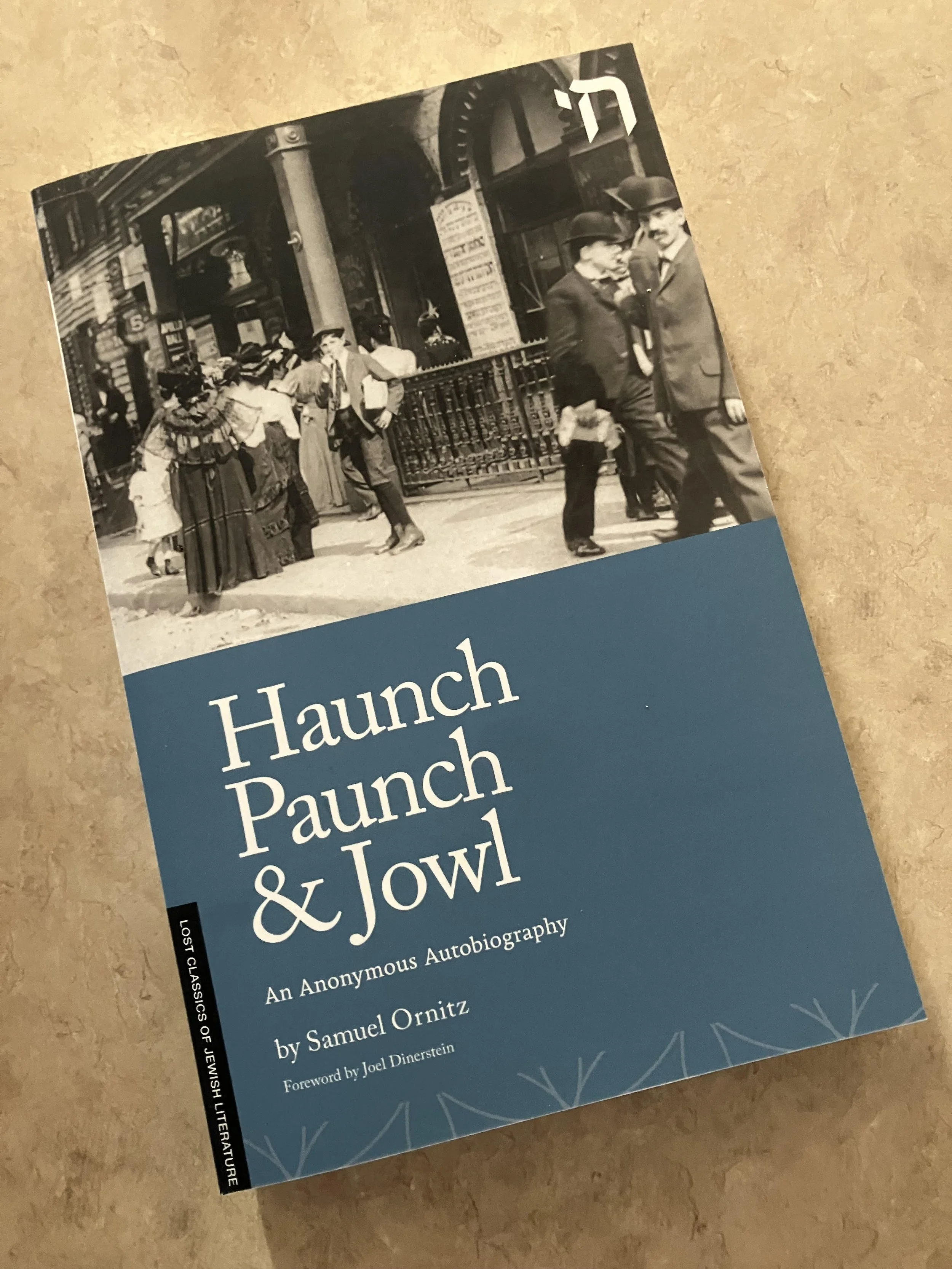

The first book of my new series, Lost Classics of Jewish Literature, is out: Samuel Ornitz's Haunch, Paunch, & Jowl (1923), a novel first published with the subtitle, “A Novel of Gangsters and Politics.” The novel provides a panorama of the first generation of Jewish immigrant life on New York's Lower East Side through a cohort of young men and two women: the struggles between religion and secular success, socialism and capitalism, tradition and modernity. Marketed as a real-life autobiography, the novel became a best-seller as an exposé of political corruption.

This novel of ethnic politics has been misinterpreted for a century, at first repudiated by rabbis for its irreverence towards Judaism, and more recently by Jewish literary scholars for its savvy, corrupt pro-capitalist protagonist, Meyer Hirsch. I wrote the new introduction through extensive archival research on the author: Samuel Ornitz was a lifelong labor activist and social reformer later blacklisted — and imprisoned — as one of the Hollywood Ten during the McCarthyist era. Ornitz clearly intended for Meyer Hirsch to be a negative example of assimilation for Jewish immigrants, yet Hirsch's compelling voice and choices still speaks American truths about poverty, social mobility, and identity politics.